SA is losing up to 35% of its water supply. For every percent of water that becomes unusable in SA, 200 000 jobs could be lost, resulting in a 5.7% drop in disposable income on a per capita basis and a 5% increase in government spending. These figures form part of the Uasa Economic Impact Study into the South African water crisis, and paint a dismal picture of the state of water management in SA.

This problem is not exclusive to SA. Worldwide, as much as 60% of water is lost due to leaky pipes, costing the global economy $14 billion every year. Should the world continue to waste water in this way, we will run out of water by 2040.

According to IBM's worldwide water subject matter expert, Carey Hidaka, the average citizen may be unaware of the extent of this wastage. This makes it important to engage citizens with the issue so that they will be more motivated to get involved, he says.

"When you flush the toilet, you don't think about where the water goes. When you turn on the tap you expect the water to be there. When it's not there, or when there are problems with the water, that's when people really react, and should cities not act, that is where we are headed."

Crowdsourcing - the second coming

According to IBM, about one-third of current urban water can be saved by using water-saving technologies. Combining these technologies with the efforts of everyday citizens has the potential to boost conservation efforts.

In 2012, Bill Gates turned to the public to help him solve a water-related problem. Gates wanted normal citizens to help him reinvent the toilet, and in doing so, to improve the lives of millions of people across the globe who do not have access to proper sanitation. The challenge formed part of the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation's Water, Sanitation and Hygiene programme, which focuses on the development of technologies that will improve sanitation in the developing world.

The top prize was awarded to a solar-powered toilet from the California Institute of Technology, which generates hydrogen and electricity. A concept from the Loughborough University in the UK, which produces biological charcoal, minerals and clean water, took the runner-up spot.

For Paul Brody, global industry leader for electronics at IBM, while crowdsourcing challenges such as these may have been around for some time, they have experienced a "second coming" of sorts in recent years. According to Brody, the introduction of funding Web sites, like Kickstarter and information archives like Wikipedia, which function through contributions from the masses, has made collective collaboration the norm. "While crowdsourcing may not be new, it has matured greatly," he says, adding that he believes changes in the size, scale and scope of problems that can be addressed in this way is the reason behind this resurgence.

As people become more comfortable with crowdsourcing as a concept, this means of sourcing services, ideas, or capital becomes more prevalent, says Brody, noting that people are starting to engage with crowdsourcing projects, and companies are getting better at executing them.

For IBM, tapping into this method of gathering information proves helpful in its water conservation efforts, as the company is able to collaborate with an immeasurable amount of people. These interactions allow IBM to gain further knowledge about problems and formulate possible solutions.

Citizen science problems create challenges because the aim is to have large numbers of people out in the field collecting data that can be used in interesting ways, says Jeffrey Pierce, manager of mobile computing research at IBM Research. "But if you have a lot of people capturing data, you have a lot of data that you have to deal with, so you need to be able to store it somewhere and efficiently compute on top of it," he says, adding that partnering with a brand like IBM will enable companies and cities to do so.

Every phone a sensor

According to IBM, the future of the world's water supply may lie in the palm of your hand - in the mobile devices we carry around with us each day. As part of its Smarter Planet campaign, IBM is working with communities around the globe on initiatives that use these devices in conservation efforts.

Over 1 000km of creeks span the city of San Jose, California. Due to limited resources, the monitoring of these waterways proves challenging.

In 2010, IBM Research and the city of San Jose collaborated to develop a crowdsourcing application that would allow citizens of San Jose to assist in the monitoring of these water systems. Dubbed "Creek Watch", the application allows citizens to monitor the watersheds in their area and report on water conditions.

For Christine Robson, the lead scientist for the app, the goal was to enable everyone and anyone to walk up to a creek and do something to help their local watershed. App users need simply snap an image before answering a few questions about water flow rate, water level and the amount of garbage in the area. "No expertise or training is required. This is an exercise in crowdsourcing, where every individual is encouraged to become a citizen scientist and get engaged with their environment."

Creek Watch takes advantage of mobile crowdsourcing, says Robson. "Every mobile phone is a sensor," she says, adding that devices with GPS functionality allow for location-based reporting. The city of San Jose has already used the data to better organise pollution cleanup efforts.

IBM Research then aggregates reports and makes the data available to interested parties via an interactive map or downloadable spreadsheet. According to Carol Boland, a watershed biologist for San Jose, the collaboration marks the first time the city has endorsed citizen science. "One of the things that new technology can do is engage the public in innovative and more convenient ways."

Traditional management involves sending city officials to monitor any water-related concerns, which is costly and time-consuming, notes Hidaka, adding that implementing collaborative solutions to solve these problems has proven invaluable for communities like San Jose. The application has spread beyond the Californian community, with over 4 000 users in more than 25 countries.

"This kind of initiative can easily be replicated in South African cities," according to IBM SA's Smarter Planet spokesperson Ahmed Simjee. "Water challenges are growing, but we are entering the age where big data and advanced analytics will enable us to change and better optimise the way that water systems operate. Yet fundamentally, technology can do little without the will of humans to co-operate, to understand that only together can we solve these challenges in sustainable ways."

Water Watchers

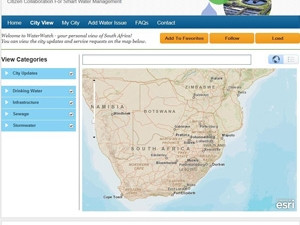

To commemorate World Water Day on 22 March, IBM debuted a similar crowdsourcing concept in SA. IBM and the City of Tshwane teamed up to introduce "Water Watchers", a mobile application that can be used to report water-related issues.

According to Simjee, an investigation conducted by IBM in 2012 found the City of Tshwane was losing R300 million rand a year due to non-revenue water wastage. "With around one million new residents to urban cities in SA every 10 years, it is becoming more feasible to leverage existing technologies (in most cases, mobile devices, smartphones, and broadband access) and co-create smart civic applications that can help improve public service delivery in our cities," Simjee notes.

"This kind of a project is driven by citizen collaboration, whose feedback is integral for the success of the project," says Robert Thimsen, IBM Worldwide Smarter Cities technical sales leader, adding that the app serves as a feedback mechanism in that it enables citizens to communicate with the government.

The collaboration saw IBM use big data to prevent water wastage via a 30-day crowdsourcing project. The initiative allowed for the capturing, sharing and analysis of information about SA's water distribution system. Unlike the Creek Watch app, the South African version boasted additional features, which allowed citizens without smartphones to report water leaks, faulty pipes and general water-related concerns via SMS. "We have enough water, we are just not using it very smartly," says Simjee.

The app is similar to Creek Watchers in that users had to take a photo of the problem and answer three questions about it. This data was then uploaded in real-time to a central database. The information generated throughout the initiative, which ran from 22 March to 30 April, will be analysed and aggregated into a "leak hot spot" map of SA.

According to IBM data, the Water Watchers portal received roughly 745 346 hits, 311 477 of which were in SA. There were 16 612 unique visitors to the site during the project, and the Water Watchers app was downloaded 324 times. IBM also conducted social sentiment analysis over the campaign period. The general sentiment towards the project was positive, and IBM also found that as it encouraged citizens to assist government with water problems, their perceptions of government's service delivery improved.

"We were really pleased with the response to the Water Watchers initiative, from the city, the media and government," said Simjee. "There was even a positive response from organisations from other continents looking at related or similar problems. The initiative sparked a flame in those who want to do something and make a difference."

While IBM ran the pilot project, Thimsen notes it is up to cities to embrace this kind of initiative. Cities will need to integrate this technology into their management procedures in order for the value of this data to be truly realised, he says.

"The next World War will be over water," Simjee says. "We have to be smart about our management of this resource, should we want to avoid this."

"Municipalities have shrinking budgets, which means they have to do more with less, and the only way to do that is to become more efficient," says Hidaka. "The amount of fresh water in the world is the same now as it was when the dinosaurs were around, and as the global population increases, water scarcity becomes more and more of a problem."

Share