Teen social media celebrity Essena O'Neill has multiplied her fame by publicly denouncing and deleting the social networking accounts on which she built her following.

The Australian health and fitness blogger, whose social media attention attracted modelling contracts in Australia and the US, has since generated furious conversation about social media celebrities and what goes on "on the other side of the screen".

In a series of minimally-edited videos, O'Neill reveals that despite her picture-perfect life, she was depressed and unfulfilled. She talks about the hours of artful construction that go into a "candid" Instagram shot, and uncovers how scores of successful Instagrammers are secretly paid by companies to post photographs of themselves using particular products.

In one video, she speaks of how her social networking obsession began in her early teens, when she was quickly led to believe that garnering large numbers of likes and followers on social networks would validate her and make her happy. O'Neill continues that as she became more popular online than she had ever anticipated, she grew less and less satisfied with her ever-growing following, permanently "looking up" to try and grow it further and never appreciating what she had achieved.

'Candid' or crafted?

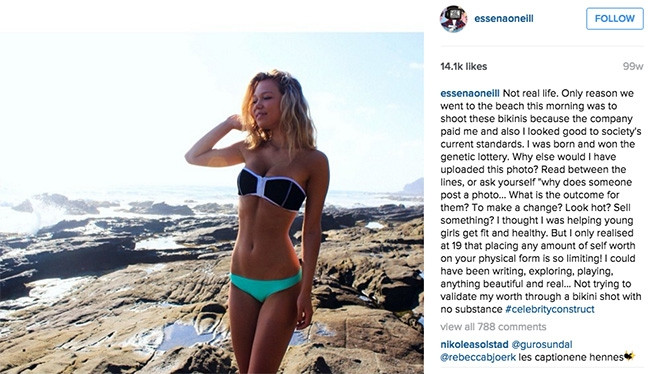

Before deleting her Instagram account entirely, O'Neill deleted over 2 000 photos that "served no real purpose other than self-promotion", and re-edited the captions to the small number of remaining posts, telling the "real story" behind each photo; for example, how long it took her to create the shot and how she had felt about it.

"Took over 100 in similar poses trying to make my stomach look good. Would have hardly eaten that day," she says of a bikini shot. Of a grainy, generic selfie: "I edited this one selfie for ages on several apps - just so I could feel some social approval from you."

"It's not as simple as posting a few photos of beautiful food, new clothes, luxury items," said fellow fitness blogger Kayla Itsines in an Instagram post responding to O'Neill's revelations. "On my account... you don't see a lot of things... the 5am wake ups, the late nights, the constant bullying, the lack of support and understanding of friends, the stress..." Itsines confessed.

Bought and paid for

O'Neill's captions also shed light on how many "casual" Instagram photos are actually paid product promotion. "Not real life. Only reason we went to the beach this morning was to shoot these bikinis because the company paid me and also I look good to society's current standards," she wrote of one photo. "Paid promotion of a tanning product. Only wore workout wear for the photo," she says of another.

The teen is not the first to draw attention to the practice of undisclosed advertising among bloggers and social network users. In August, a Kim Kardashian selfie removed by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) generated global conversation about the regulation of advertising by bloggers and social media personalities.

The FDA removed Kardashian's selfie because it did not adhere to drug advertising laws, and was quickly compared to the UK's Advertising Standards Authority (ASA), which had banned several YouTube bloggers' videos for insufficient disclosure of advertising.

In an action bridging the gap between advertising law and the new and uncertain territory of social networks, the ASA released a set of specific guidelines for vloggers, making clear that social network users can be held accountable for their advertising practices similarly to publications and broadcasters.

The Advertising Standards Authority of South Africa has yet to release specific guidelines for advertising via social networks, although it states that "advertisements should be clearly distinguishable as such whatever their form and whatever the medium used".

New niche

"Advertorial on social platforms is still a relatively new space," says Mike Sharman, MD of Retroviral, adding that media regulation is still catching up to the new advertising configurations social networks have spawned.

Brands target and pay specific bloggers and personalities to advertise their products because these individuals give them access to a niche following built around specific interests and tastes, explains Sharman.

When advertising content - disclosed or not - is obvious and disruptive in that it looks very different to the rest of the user's posts, followers tend to become bored or frustrated and turn away from an account, says Sharman. Yet if a user constructs an undisclosed advertisement themselves, camouflaging it in their unique "visual language", this can be very deceptive, he adds.

While social media personalities should be allowed to gain financial reward for the work they have put into building an audience, it is important that advertising is disclosed, Sharman says. Users trust the personalities they follow, and these personalities should respect this trust by being honest with their followers, he adds.

Something else

O'Neill has deleted her YouTube, Instagram, Snapchat and Tumblr accounts in favour of a Web site on which she posts videos critically discussing her experiences. She uses Vimeo for her videos because it does not prioritise views or followers in the same way as YouTube does, she says.

"I don't agree with social media as it currently is. Please, please, can someone make something that isn't based on views, likes, and followers?" O'Neill implores.

While Sharman notes O'Neill's point, he is doubtful as to whether such a social platform could become a massive success. "It's an ego-fest," he says of the rapid rise of social networks, posing that shallow validation metrics such as likes are central to why people use them.

Beme, for example - a "like-less" social network similar to Snapchat - has not gained very much traction, notes Sharman. And despite its praise from O'Neill and indie filmmakers, Vimeo is hardly the video giant that YouTube - with its accessible views, likes, and dislikes - is.

Share