South Africa's low-income consumers are suffering the most when it comes to high data costs.

New figures from a bi-annual report from the Independent Communications Authority of South Africa (ICASA) clearly show there is a major difference between the cost per megabyte (MB) of data in different sized prepaid bundles, which inevitably favours the rich over the poor.

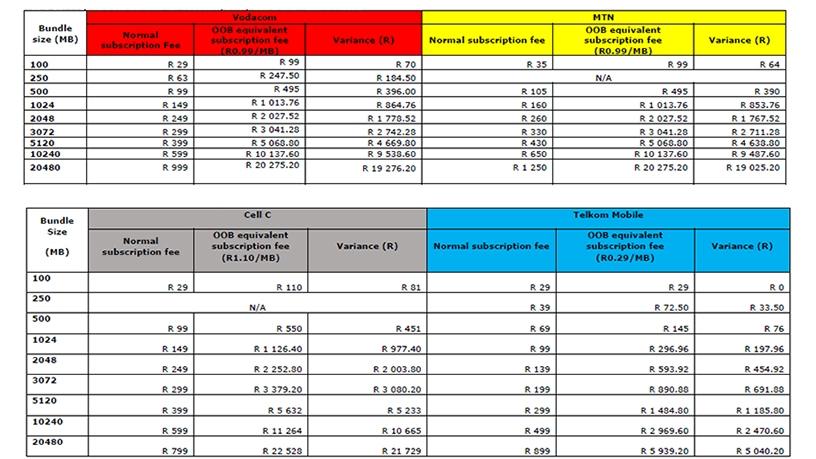

The report is an analysis of tariff notifications between 1 July and 31 December 2017, and compares the price of prepaid data bundles and out-of-bundle (OOB) rates for SA's four mobile operators.

"The unit cost of data rapidly decreases as the size of the bundle increases; ie, the subscriber received more data per rand amount as the bundle size increased," ICASA says.

This phenomenon in itself disadvantages low-income users who can't afford to buy bigger bundles and enjoy the savings they bring.

According to the data, a Vodacom customer who purchases a 100MB bundle will pay an in-bundle rate of 29c/MB. If they can afford a 1GB data bundle it will cost 15c/MB, but a customer who buys a 20GB bundle will pay just 5c/MB.

The same can be said for MTN, which charges an in-bundle rate of 6c/MB for a 20GB data bundle, but 35c/MB for a 100MB bundle. Telkom Mobile's in-bundle rate is 29c/MB for a 100MB bundle, 10c/MB for 1GB and drops to 4c/MB for a 20GB bundle. Cell C's in-bundle rate is 15c/MB for 1GB and 4c/MB for a 20GB bundle.

Even 100MB is probably too expensive for many low-income households which often buy the smallest possible bundles at an even higher cost per MB.

Koketso Moeti, amandla.mobi founder and campaigner, explains that research conducted by academics at the universities of Witwatersrand, Cape Town and Rhodes, among low-income consumers, shows average and low-income consumers are purchasing data in much smaller quantities than 1GB.

"It suggests these consumers are buying data in quantities as low as 20MB to 30MB. Some of these consumers are using mobile data without buying data bundles because they have less than the R5 needed (on Vodacom) for the 20MB bundle," she says.

The ICASA report shows some operators have recently raised prices for small bundles and dropped them on big bundles, which further exasperates the problem.

At the end of last year, Cell C, for example, increased the price of its 100MB prepaid data bundle by R10, from R19 to R29, the equivalent of a 52.6% increase in price. At the same time, it dropped the price of a 20GB data bundle by 27.3%, from R1 099 to R799.

"This affirms our contention that low-income consumers are paying disproportionately high charges and are not seeing benefits of competition in comparison to high income consumers who are able to buy larger quantities of data," Moeti says.

"It's the old story of rewarding the well-off for being well-off and punishing the poor for being poor. If operators can't wake up to the moral obligation in a country like SA, the regulator will have to do their waking up for them," adds World Wide Worx MD Arthur Goldstuck.

He says there are really two realities behind data costs in SA; the first is for the well-off who are able to afford contracts and large bundles.

"For them, data costs have fallen dramatically in recent years. The reason is simple: by providing an incentive to buy large bundles, the operators are able to lock in revenue upfront. Because the lower-income groups buy in very small increments, or use data off their airtime, they are not an attractive market for the operators.

"Because this [low-income] segment also doesn't have buying power, it does not make a massive difference to the network's average revenue per user if a customer in this segment moves to another network; there is little incentive to offer incentives to stay," adds Goldstuck.

By increasing costs for small bundles, operators are effectively blocking low-income consumers from going online as for many the only way to access the World Wide Web is through their cellphones.

"This limits the poor's ability to access the Internet, which is needed to keep in touch with loved ones, find opportunities, register a business, and in provinces like Gauteng, apply for public schools. We are also seeing government services increasingly have an online component; the convenience of which isn't being experienced by low-income users," Moeti adds.

She points out government and business are increasingly becoming more responsive online and it is easier to access information for flood warnings, etc, "which means those who are less connected are being denied critical services and/or information".

The #DataMustFall movement began in 2016 and reached all the way to Parliament's portfolio committee on telecommunications and postal services.

In July 2017, ICASA began an inquiry into the cost to communicate and the Competition Commission followed in August with its own inquiry into the high price of data services in SA. The ICASA inquiry is due to be completed this month, while the Competition Commission will be done by August 2018.

However, Goldstuck believes it's now time to stop calling for "the non-nuanced fall of data prices" but rather says data prices need to fall for the poor.

"The cost of living, shortage of jobs, and low-paying work combine to make every additional rand a burden. Since communications is a basic human need, the poor are in effect further punished for being poor by having to pay more than those who are well-off. This is not only economically unjustifiable, but also morally unjustifiable," Goldstuck adds.

Moeti proposes that ICASA sets a restriction on the maximum difference allowed in pricing per MB between small and large bundles, for bundles of the same or similar duration.

"For example, no more than twice the difference in pricing. However, in this scenario the poor still pay twice as much as those who can afford larger bundles, therefore the ideal position would be no difference in pricing between big and small bundles per MB," she says.

Out-of-bundle outrage

Another contentious issue is the huge disparity between in-bundle and OOB pricing by operators. Moeti says for smaller bundle users, the notifications received about data depletion are inadequate on some networks.

"This makes low-income users particularly vulnerable to OOB rates, which are expensive. There's been a massive cut in these prices, the most recent being Vodacom's cut to 99c last year. But even with these reductions, by the time a user has spent on 1GB of data it amounts to R990 while there are packages that are 150x cheaper for contract users, which poor people are excluded from."

ICASA has in the past said the price differentials between in-bundle and out-of-bundle data rates "are excessive". Figures from the newest report show the percentage variance between in-bundle rates and OOB rates can be as high as 2 720% (Cell C); 1 930% (Vodacom); 1 522% (MTN); and 561% (Telkom).

"The problem is that the poorest of the poor use data off airtime, which is by definition out-of-bounds. As a result, they are paying exorbitant rates which also mean they limit their usage very strictly. This in turn means they are unable to explore the possibilities of the Internet or apps, and are excluded from the digital economy," Goldstuck explains.

Share