Microsoft has released a series of technology updates, largely aimed at cloud and enterprise computing, with many new features added to Windows Server 2012 R2 (due to hit the shelves on 18 October. I'll look more closely at the new features, particularly in R2, in the future, but first I'm going to look at Microsoft's cloud strategy, since the company has been under pressure to flesh out its cloud offerings in the face of a rapidly evolving competitive market.

I spent a week closeted with Microsoft executives and engineers at the company's HQ in Redmond, looking at products and features, and discussing strategy. So, here's an insider's view of Microsoft's roadmap for enterprise computing in the cloud era. It's worth noting upfront that a lot of this is contingent on Microsoft not dropping the ball, something it's struggled with in some areas, and of course, its major competitors have strong, and in some cases more mature, strategies for cloud.

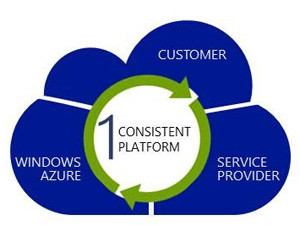

Microsoft is evolving its entire product portfolio towards its relatively new "Cloud OS" vision, articulated by Satya Nadella, who leads Microsoft's cloud and enterprise division. Cloud OS is the company's vision for enterprise IT, unifying server management, application delivery, identity management and data storage seamlessly across internal data centres, hosting providers and Microsoft's own Azure public cloud ? the company has painted a picture of customers managing resources seamlessly regardless of their geographic location, taking advantage of whatever combination works best without compromising on features or switching management paradigms.

But that is a mammoth undertaking, one which has required the complete re-engineering of the company, never mind the products. When Ballmer announced the "One Microsoft" initiative mid-year, it was intended to refocus the company's resources, mindset and market engagement. Cloud computing was one of the four engineering disciplines identified as focal points for development (the others are operating systems, applications, and hardware). And across those pillars, a far greater degree of collaboration was mandated, to avoid the infighting of the past and start to deliver services which operate smoothly together.

When Microsoft first published its Cloud OS vision, many observers wrote it off as implausible. As recently as August, Gartner positioned Microsoft in the lower right in its cloud IaaS Magic Quadrant: lots of vision, but lacking the ability to execute. Server 2012 R2, in other words, has to be a major milestone in validating that strategy, far more than merely a point release, which is why the emerging feature-set is worth a closer look.

Hard times

It's tough to be Microsoft right now. Even disregarding the strategic missteps it's made under Ballmer, the company has some big challenges in the new era of cloud services. It wants to position itself alongside the new wave of cloud leaders ? the likes of Amazon, Google, Salesforce.com. It needs to strengthen its competitive offering against EMC (in which family falls virtualisation incumbent VMware) and Oracle. But it can't abandon the long tail of existing users, which run the gamut from high-end enterprise data centres to mom-and-pop SMEs. And it has to look after its channel, system integrators, and developer community, many of whom are eyeing the cloud with either naked ambition or naked fear, but needing plenty of support either way.

Making matters worse is the company's need to be in every market at once. Historically, that would have sounded like Microsoft hubris, but today it is simply a requirement of Microsoft's vision. Instead of fighting several separate fronts, Redmond is trying to redefine the playing field. If it fails, well, Microsoft will simply be roughly where it is today: with its server and tools division still making most of its money, but a worrying lack of relevance on the horizon.

In Microsoft's favour is the market's leaning towards private and hybrid cloud: concerns about privacy and data sovereignty are just the tip of the iceberg. There are good reasons to keep compute resources on premise, and many organisations were balking at the notion of committing too quickly to the cloud. Hybrid cloud - taking advantage of cloud technologies in-house and blending them with off-premise cloud services - gives an evolutionary rather than revolutionary strategy. And if you're Microsoft, that means you get a chance to evolve the ecosystem with your customers, rather than hoping you'll be one of the candidates after the revolution.

Microsoft understands it cannot own enterprise computing, but it can remain the glue tying it all together. There's good money in glue.

Microsoft has realised it has lost the fight to control the enterprise computing infrastructure from top to bottom, and is strategically repositioning for a new battleground, which will see Microsoft as the coordination centre for heterogeneous environments. Much of this development is already in play: the company has built and is steadily enhancing its support for Linux virtual machines, creating open source management tools which integrate neatly into Systems Center but could just as easily be leveraged by third parties. Or to manage VMs in competing IaaS environments, for that matter: Microsoft would prefer to see its own offerings adopted but is happy to play nice alongside the competitors.

The question for Microsoft, then, was how to evolve the enterprise IT ecosystem to fully embrace the cloud, without leaving the legacy behind? BYOD and mobile computing has shown one way: users are driving IT, and by turning the spotlight on the user, Microsoft already has a foothold: Active Directory.

Identity crisis

Active Directory is a key technology for Microsoft, having established itself as the dominant directory service and a central component in user and device management for a majority of organisations. Microsoft intends to leverage that momentum, offering tools to enhance both device management and application delivery while extending into the cloud, under the unifying umbrella of user identity management. "User-centric computing" is the term the company uses to describe its strategy, and the idea is likely to resonate with end-users and administrators both. It is also clearly targeted against EMC's RSA division, particularly with two-factor authentication a major area of improvement in the AD suite.

Late to the party? Microsoft and the cloud.

1990s: Application service providers appear, hosting existing software solutions

1997: NetCentric tries to trademark "cloud computing"

1999: Salesforce.com opens for business

2006: Amazon Web Services - the EC2 engine was developed in Cape Town

2008: Google App Engine launches

2008: Not everyone's a fan: Oracle CEO Larry Ellison criticises cloud computing as "complete gibberish"; Richard Stallman describes cloud computing as "worse than stupidity"

2008: Microsoft first announces Azure

2009: EMC and Cisco form VCE Corp, a JV to deliver cloud products and services

2010: Windows Azure Platform commercially available

2011: Oracle Public Cloud debuts

2012: Azure offers full IaaS

2013: Windows Azure Pack released for Windows Server

So, for example, Microsoft's cloud tools allow third-party apps to leverage single sign-on with AD-managed credentials, provided the app uses standards-based authentication or allows some degree of integration. An IT administrator, for example, can automatically provision and de-provision a Salesforce.com account alongside a corporate identity. Users can attach existing cloud service accounts (such as those irritating cloud services which users self-provision) within the portal, allowing them to be brought into alignment with enterprise policies. Even a company Twitter account can be federated, allowing users to access it with their domain credentials. Microsoft has over 200 third-party cloud apps supported, and is targeting 500 by the end of 2013. In the same portal interface, a user can access external apps, internal Web apps, or proxied applications, without knowing the difference.

That's a compelling idea, but it does still need work on both sides of the fence (Microsoft and the cloud ISVs), particularly in supporting native apps on devices, not just Web apps. You also can't manage multiple instances (like one user with several Twitter accounts) yet.

Clearly Microsoft wants to establish Active Directory (particularly in Azure) as the central identity provider of choice, but since its efforts all leverage standards like OAuth, it actually shouldn't matter whether an app prefers to use a Google ID or an AD one ? if Microsoft gets it way, it will imply stronger standards support throughout the industry, and the company will be competing on the strength of its management tools and integration, rather than the power of its silo.

For the admin, Web-based tools allow for AD management whether the domain is cloud-based or not. With app and device management integrated in the Web interface, you'd be excused for wondering why an admin would bother using the server's own AD interface at all for everyday tasks - the newer Web components are slicker, more responsive and better focused.

In the medium term, Microsoft fully expects Active Directory to migrate rapidly to the cloud ? isolated on-premise deployments will be anomalous, with most customers either choosing to use a hosted option either as the primary source, or as a cloud extension, and again, the company wants the border between the two to be blurred to the point of invisibility. Multi-factor authentication is an example of this: you can use a mobile phone (call or SMS) to confirm identity for domain logons, tied to AD, but provisioned through Azure. The company hopes AD will become a central tool for managing the entire ecosystem of devices, apps and users, regardless of who manufactures the device or hosts the app.

Azure is where Microsoft is up against the stiffest competition, and its role in the Cloud OS strategy doubly so.

Watch this space: Microsoft is going to aggressively push this user-centric idea, and build out the capabilities of Active Directory in Windows Azure and Windows Server. That will be closely tied to device management (as deeper interaction with Windows Intune shows) and application delivery.

Management across borders

A great deal of work is going into server management as well. Microsoft wants you to manage everything through System Center, and to do that, it has to play nice with more than just Windows. Microsoft has pushed VM drivers into the mainline Linux kernel, for example, and published open source management tools to integrate Linux servers into System Center. As the tools converge, the line between managing servers on premises, off premises, and in virtual environments becomes blurred, and the Cloud OS vision becomes a step closer.

Microsoft has also worked with network manufacturers to extend its logo certification programme to network devices, and its vision of software-defined networking (SDN) predictably moves network configuration to the server's control. Every vendor has a different take on SDN, and some of them are more mature than Microsoft's, but Redmond's idea is, in short, for an administrator to define network behaviour for a virtual environment which can then be layered on to a cloud without reconfiguring VLANs or reassigning addresses. Network configuration happens automatically, which may not thrill network engineers, but it is intended to make deployment of complex cloud environments easier and more robust.

Windows Server's interfaces continue to evolve - the drive remains towards simplicity, based around server roles, with advanced tasks offloaded to PowerShell, Microsoft's command line environment. This allows the company to find a balance in providing an interface suitable for everyday admins while delivering the advanced features experts demand. It also makes scripting much easier, and encourages repeatability. And it opens the door for third parties to build additional management tools which simply sit atop PowerShell. On the downside, it can mean jarring transitions from GUI to command line and back, and extra hoops to jump through in troubleshooting botched configs. R2's useful "desired state configuration" extension allows admins to push configuration goals to servers, letting the subsystems do the relevant configuration: PowerShell may be a tool for expert users, but more and more admins will find themselves learning it to adjust systems to their needs.

Mobile device management and security are other areas where Microsoft is pushing hard. Intune has already been integrated with Configuration Manager, and deeper integration is coming. Config Manager looks after some 70% of enterprise desktops, Microsoft execs tell me, and the goal is to extend that into the cloud with new devices. Again, the focus is on users, not devices - a change described as shifting from controlling users to enabling them. Workplace Join, for instance, is a new feature which helps users connect devices to domains, offering two-factor authentication and single sign-on without giving up control of the device.

Remote access apps for iOS, OSX and Android are coming too: Microsoft is delivering a variety of mechanisms to extend enterprise applications to end-users regardless of their device and that, coupled with the easier enrolment processes, will be a major improvement for users and admins grappling with BYOD.

A NAS by any other name

An area where Microsoft is investing very heavily is storage performance in Windows Server. On the face of it, that's in response to customers who are concerned about the high cost of deploying and managing enterprise storage, but underneath there is a definite jab at EMC. NAS servers, Microsoft asserts, are just servers with "storage" on the front and extra zeroes on the price tag. Replace them with Windows Servers, is the cry, and while the argument is that customers will save money, the point is that the framework will migrate to Microsoft. Storage vendors will dispute this hotly, of course, and the growth of packaged storage solutions may mean Microsoft has an uphill battle, but storage prices are a good way to start conversations with customers, and the end result is more likely to be a combination of the two: Microsoft won't unseat the big storage players, but it can help customers get better efficiency and performance from their storage investment.

Competitive barbs aside, Microsoft has done a lot of work both improving storage performance (and has the IOPS numbers to prove it) and has started to roll out advanced features in its Storage Spaces framework. Automatic tiering - moving data between SSD and spinning disks - is supported to improve performance and resiliency. Improvements to deduplication now support VHD, greatly reducing disk overhead for virtual desktops. New sharing mechanisms are available: "Work Folders" keeps files in sync between shared folders and mobile devices. This is an area where some rationalisation may follow - Microsoft now supports multiple ways to share and synchronise data between devices, servers and the cloud, and there are undoubtedly areas of overlap.

Kicking IaaS and taking names

Virtualisation, and cloud hosting, is a critical chapter of the cloud story. Microsoft's decision to establish Azure as an IaaS service supporting VMs, rather than a collection of components for building Web apps, has been a major factor in Azure's growth. And Hyper-V, Microsoft's virtualisation hypervisor, has been enhanced for R2 with new capabilities and management options, but a major development is simply the timing of another announcement: Oracle has certified database workloads for Windows Server in virtual environments, and Oracle Linux (the RHEL version, not the "unbreakable" kernel) in Hyper-V.

The Windows Azure Pack, which brings Microsoft's cloud code into enterprise data centres, is freely available for Windows Server and is used as an engine to drive innovation between the server and cloud sides of the business. In a very real sense, Azure Pack is the glue holding a lot of Microsoft's cloud technology together, incorporating cloud provisioning and management in a consistent interface across private, hybrid and public clouds. Many of the underlying technologies are already baked into the server platforms and Azure itself: the Azure Pack offers a layer bringing the many components together for administrators

Microsoft has realised it has lost the fight to control the enterprise computing infrastructure from top to bottom, and is strategically repositioning for a new battleground.

Azure is where Microsoft is up against the stiffest competition, and its role in the Cloud OS strategy doubly so. Azure, extending through the data centre, puts Microsoft at odds with everyone in the IaaS/PaaS/SaaS spectrum. Many of the competition are also partners, of course, and Microsoft is hoping to position its suite as the management framework within which many competing services (its own among them) engage a customer. And that is the key to the cloud strategy here: Microsoft understands it cannot own enterprise computing, but it can remain the glue tying it all together. There's good money in glue.

Microsoft is baking Azure code more deeply into Windows Server, unifying the management of servers and cloud resources, and also using Azure itself as a delivery engine. Standing up a VM or a packaged app on Windows Server or in Azure, managing resources, and delivering access to users, can be done through the same interfaces and tools.

Apps and services

Microsoft has made a good start in cloud apps and is now pushing hard to make sure its portfolio is as cloud-friendly as possible. Doing so gives it multiple bites at every cherry: delivered as a service in Azure, in a customer VM in Azure, hosted through a channel partner, or on-premise.

Microsoft is positioning Azure as the framework which delivers and manages the portfolio regardless of deployment type - and open to competitors' products being included in the mix.

Only the start

Windows Server 2012 predates the new vision, though some early signs were already there, especially viewed in hindsight. R2 is the first release to land in the "One Microsoft" era, and it is showing clear signs of strategic realignment, even though it's only an R2 release and not a full version. There are some rough edges and redundancies which are likely to see refinement in the future, but Azure in particular has committed Microsoft to a faster update cadence. The engineering process within Microsoft is clearly under immense pressure ? not just realigning around the new corporate vision, but adjusting to cloud-first thinking AND a more rapid delivery schedule. If the company can pull it off, it will be a realignment of epic proportions.

Next time, I'll look at specific features in more detail, and how these changes are expected to impact customers and their environments, channel partners and integrators, and the competition. Microsoft, after all, is not the only player with grand designs on the cloud.

Share