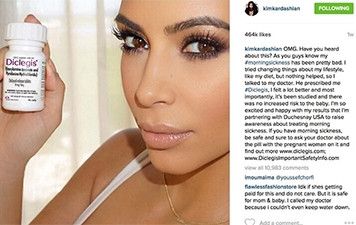

A selfie posted by reality show personality Kim Kardashian earlier this month has provoked a flurry of conversation and heightened awareness about legal and ethical issues with advertising via social media, specifically through sponsored content.

The US Food and Drug Administration ordered Kardashian to remove a selfie she posted on Instagram promoting Diclegis, a morning sickness drug, because the post was "false or misleading" in praising the drug's efficacy while omitting important risk information.

While celebrities have long been benefiting from sponsorship or endorsement agreements with brands, the accessibility of publishing via social networks means advertising regulations present a relevant concern to an increasing number of citizens benefiting from pushing paid-for content via social media platforms like YouTube and Instagram.

for vloggers

In the wake of Kardashian's banned selfie, the UK's Advertising Standards Authority (ASA) last week offered a set of advertising guidelines for UK video bloggers (vloggers), a number of whom have been called out in recent months for not being transparent enough about commercial partnerships.

In May, the ASA banned a video featuring vlogger Ruth Crilly giving makeup tutorials because the video did not sufficiently clarify that it was sponsored by Max Factor makeup. In November 2014, a number of British YouTube stars' videos for an "Oreo Lick Race" challenge were banned because they were found by the ASA to be an advertising campaign for Oreo, which was also not properly clarified to viewers.

Vloggers had approached the ASA saying they felt "under pressure" not to reveal sponsorship agreements to their viewers, said Guy Parker, ASA chief executive. Explicit guidance from the ASA could help vloggers to push back, he added.

The vlogging guidelines, published by Committees for Advertising Practice (CAP), say that a general assumption is made that any mention of a product by a vlogger is an independent decision of the vlogger as the publisher, and if a commercial relationship has impacted this decision, the vlogger must take sufficient measures to clarify this to viewers.

If the vlog's content is controlled by the marketer and written in exchange for payment (not necessarily money), it is an advertisement and must be labelled as such, says CAP.

CAP's guidelines offer specific advice for eight particular scenarios vloggers are most likely to encounter in commercial relationships. These include online marketing by a brand, "advertorial" vlogs, commercial breaks within vlogs, product placement, a vlogger's videos concerning their own products, sponsorship agreements, and free items given to the vlogger by a brand.

For SA vloggers

While the SA "vlogosphere" does not amass the millions of dollars and pounds many vloggers in the US and UK rake in annually, often through commercial partnerships, advertisers are slowly catching on to the potential value in the growing numbers of SA vloggers and viewers.

Checkers in July featured SA YouTube personality Suzelle DIY alongside SA entertainer Natani"el le Roux in a YouTube ad which attracted over 350 000 views.

The Advertising Standards Authority of South Africa (ASASA) has not released specific guidelines relating to vloggers, but its advertising code of practice states that "advertisements should be clearly distinguishable as such whatever their form and whatever the medium used".

ASASA's sponsorship code stipulates that the audience "should be clearly informed of the existence of the sponsorship".

Share