In future, humans will not need a common language in order to communicate, but will be able to converse in any language they choose, with a computer handling the burden of translation.

That is one of the long-term goals of Kamusi GOLD (Global Online Living Dictionary), an online dictionary with a difference. Rather than just providing definitions of words in every language, Kamusi ('dictionary' in Swahili) matches these definitions to similar ideas and concepts in all other languages.

Founder and executive director Martin Benjamin came up with the idea for Kamusi while researching development issues in Tanzania in 1993. He spent time in villages in remote parts of the country and needed knowledge of Swahili in order to communicate with the local people.

"I found there were no decent dictionaries out there and started thinking about how one would write a Swahili dictionary," says Benjamin. "It takes years of work and hard labour to write a good dictionary. For a market like Swahili, most speakers are only earning $1 a day, so they would never be able to afford a dictionary at a price that would pay for its production."

The dictionary originally started out as an Excel spreadsheet, with information inputted manually from an English-Swahili dictionary, which was converted to text files for people to download. This model started to become unworkable by the time they had added 3 000 words, and completely fell apart when they reached 16 000, says Benjamin. They then decided to code it onto the Web into a MySQL database, so people could contribute. "Here we are almost 20 years later; the Swahili dictionary is still a work in progress, but now we've started dictionaries in other languages also."

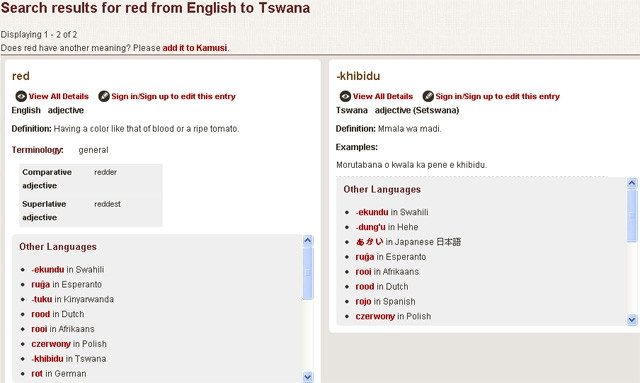

There are currently 20 languages on the site that have been completed at a demonstration level - configured for the unique ins and outs of the particular language - and 100 terms added to the parallel data set. Another 20 languages are in development. A South African translation company is donating the work for Afrikaans, Zulu and Xhosa, while the preliminary work for Tswana is already complete.

Launched on 21 February - International Mother Language Day - Benjamin sees great potential for Kamusi. "The world doesn't need another English, French or German dictionary; what we don't have are good tools for people who are not native speakers of languages like those to access knowledge.

"With this dictionary, as a Zulu speaker, for example, you'll go directly from Zulu to having all the information available to you in English, or German, or any other language. Because it's all linked on a concept-by-concept level, you would have access to all of the concepts in German, or Somali or Japanese.

"There may not be a market for Tswana to Yiddish, but we'll have that. Any combination you can think of will be there. It's not for us to predict who needs to know what from where. We produce the resource and then we open it up."

With all the data on Kamusi, Benjamin is confident they can "change the way translation works". "Imagine writing an article in your language, then publishing it in readable form in 100 languages instantaneously," explains Benjamin. "That's where Kamusi is heading."

Contributions

Kamusi relies on contributors, members and donations to do its work. The annual membership fee is $30 (about R287). Of the site's one million annual users, there are currently only 50 dues-paying members, but Benjamin is aiming for 1 000.

The key information Kamusi requires from contributors is not only a word and its equivalent in English or another language, but also a definition of that word in its own language. "For example, while it's important to know that red is 'rooi' in Afrikaans, it's even more crucial to know that 'rooi is soos die kleur van bloed' (red is like the colour of blood). You will get some kind of similarity for 'red' being referenced in a culturally appropriate way for every language you select on the site."

He assures that each entry is subject to a moderator to ensure accuracy, "so it's not the wild Wiki world". The end goal, he says, is to create a product that people will have a lot of confidence in.

ICTs and minority languages

According to Benjamin, Kamusi offers a platform that can be used to preserve languages in a more systematic and accessible way than has been available up until now.

"Once we've configured a language, speakers can add audio, video, anything that's specific to their language. They don't need a publisher or a library. They will be able to take their smartphones or tablets with them into the field and use it for literacy. Now they have this tool (dictionary) and the ability to develop grammar books, etc."

From an ICT aspect, says Benjamin, Kamusi makes the tools, data and knowledge available, with an open source licence and free access to the public. This makes it possible to document and disseminate the knowledge in a way that might be useful.

"It's a lot easier to teach a computer the things that are needed in order to do the translation than it is to teach millions of people how to speak another language," he says.

This is where Kamusi finds its sweet spot; the applications are endless. "It can be applied to anything that requires one person communicating with another person, but they don't speak the same language," concludes Benjamin.

Share